$60.12

Back Ordering

Usually wait 20 days

- Hardcover

- 176 pages

- 222 x 283 mm

- ISBN 9784865411447

- Japanese, English

- Oct 2022

Hisae Imai was an unconventional photographer. With the encouragement of a friend of her father Yasumichi, a professional photographer who ran the studio at the Matsuya Ginza department store, she made a brilliant debut in 1956 . This first solo exhibition, Daydreams, attracted tremendous attention even though at the time she had no real intention to make a career of photography. With this exhibition as a starting point, she continued to pursue her artistic instincts while also taking on fashion and commercial projects, and then she took over her father's studio when he died suddenly in 1960 . Because female photographers were a rarity back then, in 1957 she took it upon herself to start an association for women photographers. These days, the emphasis tends to be on the fact that Imai was female. However, what really distinguished her was that she was a mold-breaker who wore three different hats: she was a fine art photographer, a commercial photographer, and a portrait studio photographer. Whether male or female, this was almost unheard of in Japan.

Hisae Imai enjoyed smooth sailing as a photographer: in 1959 she received the Japan Photo Critics Association Newcomer's Award and in 1960 she received Camera Geijutsu magazine's Geijutsu Art Award. But then tragedy struck on June 1962. A taxi that she was riding in was involved in a traffic accident and she temporarily lost her eyesight. For the photographer, this was a major crisis. The accident left a scar on her face and resulted in her being rejected by her fiancé, and these things must have been painful. Nevertheless, in March of the following year she plunged into her first solo exhibition after the accident, titled Teeth--A Fantasy, and then in June she mounted her seventh solo exhibition featuring the Lone, Rose Party, and Dream Walk series. Sometime around 1965 she became absorbed in photographing racehorses and her exhibitions virtually stopped. The year 1970 marked five years since she had gone to Europe in search of horses, and there was virtually no news of her. Then, in 1975 she mounted her Hippolatry: Enchanted by Horses show, a major success that toured department stores in the cities of Osaka, Kyoto, Tokyo, and Sapporo. Afterwards, she remained active as a horse photographer, and following her death in 2009 the Japan Racing Association awarded her the Equine Culture Award of Merit.

There were the poetic early works--in which forms that combine the abstract and the literal were expressed in then-rare color photographs, as if painting a picture with a photograph--but then she was also a horse photographer, flying hither and thither around the world in pursuit of famous horses. I think that what at first glance appears to be a duality in Imai can be understood in light of the fixation on the body that is expressed in her work. The Ophelia series (1960) is perhaps the most acclaimed of her early works. It takes the tragic young noblewoman Ophelia of Shakespeare's Hamlet as its leitmotif, but the body swap is Imai's own idea. In Imai's novel reimagining of the story, just as Ophelia is singing, about to sink into the water, an old woman appears, and after talking with Ophelia they exchange bodies.

According to Imai's sister Kuniko", When she had surgery, the transfusion replaced the blood throughout her entire body, and it seems like my sister's personality changed quite a bit. Someone who had been obsessive became easy-going."This episode--in which a person undergoes a transformation after a blood transfusion--overlaps in places with her Ophelia story, in which two Ophelias exchange bodies. An old woman swaps bodies with a young and beautiful--but deranged-- Ophelia, who is unaware that she will die. Surprisingly, the body swap leitmotif had appeared in Imai's work even before the accident." [...]

Imai's first project after returning from her accident was Teeth--A Fantasy (1963). She had been creating works with teeth as a leitmotif for some time, and she brought them together for a camera magazine piece called Fantasy: Eyes and Teeth. The works that she showed at the "NON"exhibit alongside her contemporaries Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, Kikuji Kawada likewise adopted eyes as a leitmotif. After the accident, however, eyes and teeth both depict a pitiful state, painful to behold. There is little evidence of an external agent using the body for its amusement, but the photographs present bodies that are objectified; enfeebled bodies that have been punctured, battered, and injured. They express the intimacy and pain of that sensation.

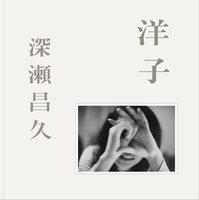

Just three months after Teeth, Imai's playfulness was once again on display when she mounted her seventh solo exhibition showcasing the Lone, Rose Party, and Dream Walk series. In Lone she uses women's faces and hair to play with colors, negative/positive inversion, and multiple exposures. In Rose Party, a voluptuous, alluring model wears a weighty crown of roses. Imai's world of free-ranging imagination unfolds in works like Dream Walk, where Yoko Kamoi is joined by other men and women looking like dodgy characters in a free-for-all romp.

During this solo show, Imai was selling the rights to use photographs for commercial purposes. The venue, the Fuji Photo Salon, had come up with this idea as a way of leveraging the gallery space. But as a result, her exhibition was ridiculed as the"money-grubbing Hisae Imai solo show." The initiative had been an attempt to strike a balance between art and commerce amid the growing commercial demand for photography leading up to the Tokyo Olympics, but it was misunderstood. The same kind of criticism was also leveled against Imai's public photograph sales at the venues where her Hippolatry: Enchanted by Horses show was exhibited. At the time, Imai was selling prints that were quickly produced by a photo lab to the public, and this became the subject of criticism.

Rather than their visual beauty, Imai may have been taken by horses due to their profound energy, grace, and tenderness, which far surpasses those characteristics in humans. For Imai, who was injured both physically and mentally by the accident, the tenacity and tenderness of horses must have been therapeutic, more than anything else. Up to this point, Imai had approached the female body through play: by transforming the body into an object or by exchanging bodies. When she was seriously hurt, rather than introspectively looking at her own body and mind in the same manner, perhaps she instead sought out something strong and beautiful outside of herself; something from the outside that would be overwhelming, and thus captivating. For Imai, this must have been horses. She grappled with something akin to being in love with the horse, a subject that was beyond her control. Rather than facing her own uncontrollable mental and physical state, she instead threw herself into pursing the uncontrollable horse as a subject. For Imai, it may have meant transforming and healing her own body by using her camera to put her entire body and soul into looking at her subjects.

Imai called her horse photographs"dream merchandise" She tried selling small prints for 8,000 yen, with the printing outsourced to a reliable photo lab that would deliver the prints to buyers within two weeks. But Imai's experiment ran counter to the ideas of the photographic establishment, which was moving in the direction of limited-edition original prints. When Imai called her own work "dream merchandise"to be sold at department stores, she was taking a completely different position from the rest of the Japanese photography world. Her highly acclaimed fine art photography book Hippolatry (1977) received the Photographic Society of Japan Annual Award, but afterwards the female photographer who had once been well-received in the photography mainstream became estranged from the establishment.

Imai was determined to sell photos at department stores because her own father, Yasumichi, had been a portrait photographer who ran the studio at the Matsuya Ginza department store. Sometime around 1954 , before her debut, Imai met Shuzo Takiguchi, an art critic who was a client of her father, to have him view her work. He encouraged her, saying that the work had potential and she should keep at it . Imai's debut exhibit, Daydreams, was shown at the Matsushima Gallery, which was across from her father's Matsuya Ginza studio. Other artists who showed at the same gallery that year included Ikko Narahara, Kansuke Yamamoto and Keiichiro Goto.[...]

Matsuya Ginza also served as the venue for the 1962"NON"show. Department stores were where Imai got her start. In an era when art museums were still largely a male preserve, perhaps Imai just wanted to sell her beloved horse photographs in department stores, which were, after all, places where there was no gap between men and women, places that evoked a feeling of happiness upon entering, and places where people could dream.

In 1962 , Imai's confidante Yoko Kamoi wrote", I am not qualified to speak about the value of her Ophelia in a professional context, but I cannot deny that I felt unease and mistrust toward the photography world, which had to wait until now, and only now, for this phantasmagoric series to be presented." These words seem prophetic, telling us that Hisae Imai--who was the most successful female photographer in the history of Japanese photography--had set out on a path that would ultimately cause her to be forgotten by the establishment. Staging her shots to create photographs that were rooted in illusion and poetry, she was a mold-breaking photographer who was also commercially successful, setting her apart from the conventional world of photography in Japan.

Extracted from the text "Re-encountering Hisae Imai"

Masako Toda