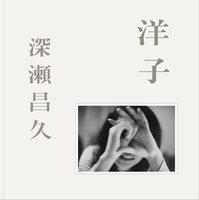

$44.35

- 228 mm × 289 mm

- 128 pages

- ISBN 978-4-86541-092-1

- Dec 2018

My grandmother's death was the impetus for me.

My grandmother suffered from Alzheimer's disease late in life. Her diary indicates that in the initial stage of the disease she became aware that she had contracted it. And from that time, as if she were gathering up the memories falling away, grandmother began to write down in detail the little everyday things that happened. The content of the three daily meals, exchanges with family members, trimming of trees in the garden, the birds and insects that gathered there...

The diary book was opened many times a day and although the words written there were certainly her own, none remained in grandmother's mind.

Grandmother was aware that time for her was losing its past and future, was without connection or direction, instants lined up, and in despair she wrote in the diary "I'm going to become someone whose life won't have meaning anymore." Finally, she forgot everything--that, the diary itself, her family, and all about herself.

And things such as grandmother's self-awareness and her innate character and abilities were also all impaired.

From my childhood I really loved my grandmother, so I felt a deep sense of loss and bewilderment to see her change so completely. I couldn't help thinking, "This can't be called living." That was because in interacting with grandmother as she was now, I was seeking the image I held inside of how she was in the past. Yet watching grandmother swaying between existence and meaning also became a chance for me to reconsider what "living" is in essence.

That was because she was indeed living and I always felt the strength of that.

So in the several years until grandmother's death, I continued to photograph her. By doing that I hoped to get close to something of the essence of "living."

I avoided searching for the grandmother of my memory in the viewfinder; instead I always tried to capture her reality at the moment. Whenever I said "Look here at me" she was able to do it, but that was all. In her worsened condition, grandmother no longer knew what a camera was, who I was, or even who she herself was.

The photographs gave an accurate picture of grandmother as she was at the time. This enabled me to confirm the fact that the person in the photographs was not just "anyone," it was undeniably "grandmother."

This "grandmother" was not the image of her that grandmother herself had developed, not the image of grandmother that had accumulated and was stored inside me, and not a new image of grandmother, but an individual presence that could only be described as "grandmother."

The photographs expressed the strength--the tenaciousness--of her "individual presence" that never disappeared for a moment, no matter what the situation.

I decided that instead of contemplating in words what "the meaning of living" is, I would try instead to photograph persons living.

For me, grandmother's portrait served as an indicator.

Like that photograph, expressing people just living as themselves.

We, who ordinarily assign meaning to ourselves and other people we place layers of meaning on to understand them, tend to perceive absence of meaning in someone as meaning that the person is empty. However, the more photographs I take, the more certain I have become that "individual presence" precedes "meaning" and is stronger.

Eventually, I began to come across objects, plants and animals, scenery, and sights that I felt "seemed to resemble people living" and photographed them guided by those feelings.

When I printed out the photographs and lined them up with portraits, I noticed that the viewpoint of "individual presence" is not limited to "people." This was also noticing that we place layers of meaning on subjects other than people that we look at. I began to aspire to take photographs that returned from meaning back to "individual presence." For me, photographing objects is the process of composing portraits.

All things change form over time, but individual presence is unchanging from birth until that presence ceases to exist. The unchangeable within the changeable...

I photographed scenery, for example a forest or a city, with the same sense as I photographed portraits. However, there is no "individual presence" of a "forest" or "individual presence" of a "city." This is because a forest is composed of trees, grass, animals, insects, and a city is composed of buildings, streets, railways, the people gathered there for various purposes--both are a composite of the interactions of many "individual presences." Still, I get a feeling of the "individual presence" of places we name a "forest" or a "city" because the interaction of their many "individual presences" connect to present a unique appearance. I also photographed portraits of those appearances.

Cities are interactions intentionally made by people. Some forests are interactions produced by nature and some are interactions produced artificially by afforestation.

So